A furniture donation was the reason to travel again to Oradea, Romania (located right on the Hungarian-Romanian border) at the end of April 2024 and to support people2people (https://people2people.ro) with various relief supplies. This service mainly takes care of Roma children, i.e. children’s clothing was a priority alongside the furniture, including a desk. So a friend was contacted who had actually put children’s things aside. My call came just in time, the things were picked up the evening before the big trip and stowed in the bus, which was thus filled to the brim.

A friend who had originally suggested the trip to Oradea was unable to come along because she had to recover from the unusually high level of office stress over the weekend. Taking a car journey of over 1000 km after a hard week at work would have been too exhausting for her. However, she donated a lot of sweets for the children, for which I was very grateful. And so I decided to take the aid supplies to Oradea alone. I had already driven to Oradea alone and knew the route. Now, however, I had learned that there was a continuous motorway to Oradea. All the better, I thought. Since I had bought the premium version of a navigation system that had already served me well as a basic version in Israel, I was sure that the new motorway route would be easy to find. Far from it, because the navigation system unfortunately did not communicate with me optimally. It needed an additional function that could only be downloaded the next time I had WiFi access (i.e. after I arrived at the hotel in Oradea).

Beyond Budapest, I used signposts to look for the route to Romania – RO. The M5 motorway leads via Szeged to the Hungarian border with Romania. Of course, it only said “to RO” and so I followed this route. After I had already covered a few kilometers on the M5, the city name “Arad” finally appeared on a motorway sign. That meant: I was heading south (Romanian border town of Arad) and not directly east (Oradea) where I wanted to go. I decided to leave the highway and head straight east on country roads. I was making slow progress and wanted to make sure I took the direct route, so I stopped and asked a group of people for directions. It turned out that I was talking to three generations of local Hungarians. The oldest man in the group hardened his features when I asked for directions to “Oradea”. He was not willing to help me. His son, who was standing with his children and wife, was thankfully more helpful and he also spoke good English. In the conversation I finally mentioned the Hungarian name of Oradea, namely Nagyvárad. Suddenly the older man’s face lit up. He now waited benevolently next to his son, who showed me the route via Püspökladány to the Romanian border on my road map. Interestingly, the son never mentioned the Romanian name of the city either. When I asked him precisely whether this was “to Oradea” (I wanted to be sure), he simply replied “this is the way to the border”. I was surprised by his evasive wording, but I was even more pleased by his willingness to help and thanked him and his whole family. It was only later that I realized the symbolic nature of the situation.

A look at the history of the region around Oradea explains the attitude of these Hungarians. All of Transylvania, including the Crişana region (named after the River Kreisch/Hungarian Sebes-Körös/ Romanian Crişul) with the Bihor district, whose capital is Oradea, was formerly part of Hungary (Bihar county, capital Nagyvárad). After World War I, the Peace Treaty of Trianon (a suburb of Paris where the victorious Allies negotiated the peace terms with the defeated Hungarians) awarded all of Transylvania to Romania. As an Austrian, I am only familiar with Saint-Germain, where the peace treaty with Austria was negotiated or dictated.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vertrag_von_Trianon#/media/Datei:Österreich-Ungarns_Ende.png

Many Hungarians are still hurt by the loss of Transylvania, and the 1918 border demarcation is seen as arbitrary and unfair (see illustration: around a third of today’s Romania belonged to Hungary before 1918). Romanian names of former Hungarian cities are a painful reminder to Hungarians of this loss. It is understandable that they use their own Hungarian names for the cities that are now in Romania.

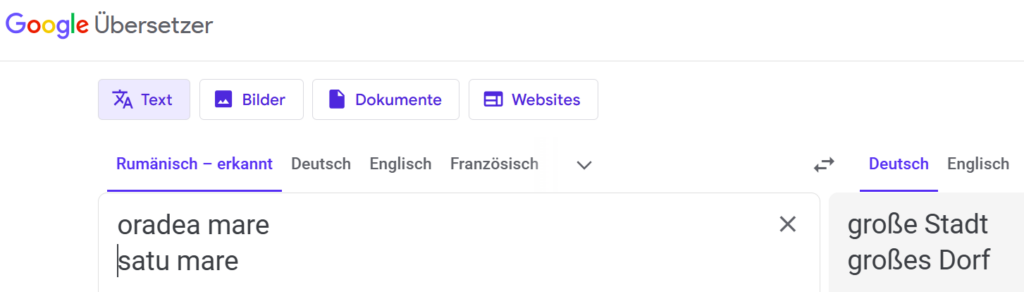

Romania, for its part, carefully chose new Romanian names for the former Hungarian cities in order to avoid any association with the Hungarian names. “Oradea”, for example, has, according to some people whose native language is Romanian, whom I asked about it, no meaning in Romanian. Until 1925, however, it was called “Oradea Mare” (the Roman Catholic diocese and the Greek Catholic eparchy are still called Oradea Mare today). A translation program translates these two connected words as “big city”.

It is clear that “mare” means “big”, because Satu Mare, for example, means “big village” for the former Hungarian Szatmárnémeti, German Sathmar. However, “city” in Romanian is “oraş” and not “oradea”. Maybe “dea” is an old suffix that was previously used for place names. Because the Hungarian name of Oradea, “Nagyvárad”, means something like “Big Castle” in Hungarian: nagy = big, vár = castle and “ad” is a suffix for place names. In addition, the Greek “varosi” and the Latin “varadinum” both mean “fortress”. Combined with the Latin “urbe”, which means “city”, the result is “fortress city”, which fits perfectly with the historical reality that Oradea/Nagyvárad was an important garrison town in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, among other time periods. The German name of today’s Oradea was Großwardein (I was quite surprised when a certain German-language navigation system once showed “Großwardein” instead of “Oradea”).

With the help of the young Hungarian’s precise route description, I drove to the Püspökladány junction, where I was able to get onto the brand new M4 motorway and reached Oradea after a short drive. The handover of the relief supplies was quick in Oradea after I had easily found the new address of the p2p association with the help of the updated navigation system. The p2p manager quickly helped unload the packed bus and thanked me for the relief supplies.

I was soon able to start the return journey, which took me through the city center of Budapest. That’s where an electric piano was loaded onto the bus, which will be used, among other things, to provide musical accompaniment to future friendship meetings of our association in Vienna.

Looking back, my trip didn’t go as I had originally expected. However, I had experiences along the way that taught me important and interesting things about the shared history of Hungary and Oradea, for which I am grateful.

Elisabeth Baumegger

(End of April 2024)