Herminengasse 6, 1020 Wien

Alexander Zaidmann

Irma Zaidmann

Charlotte Zaidmann

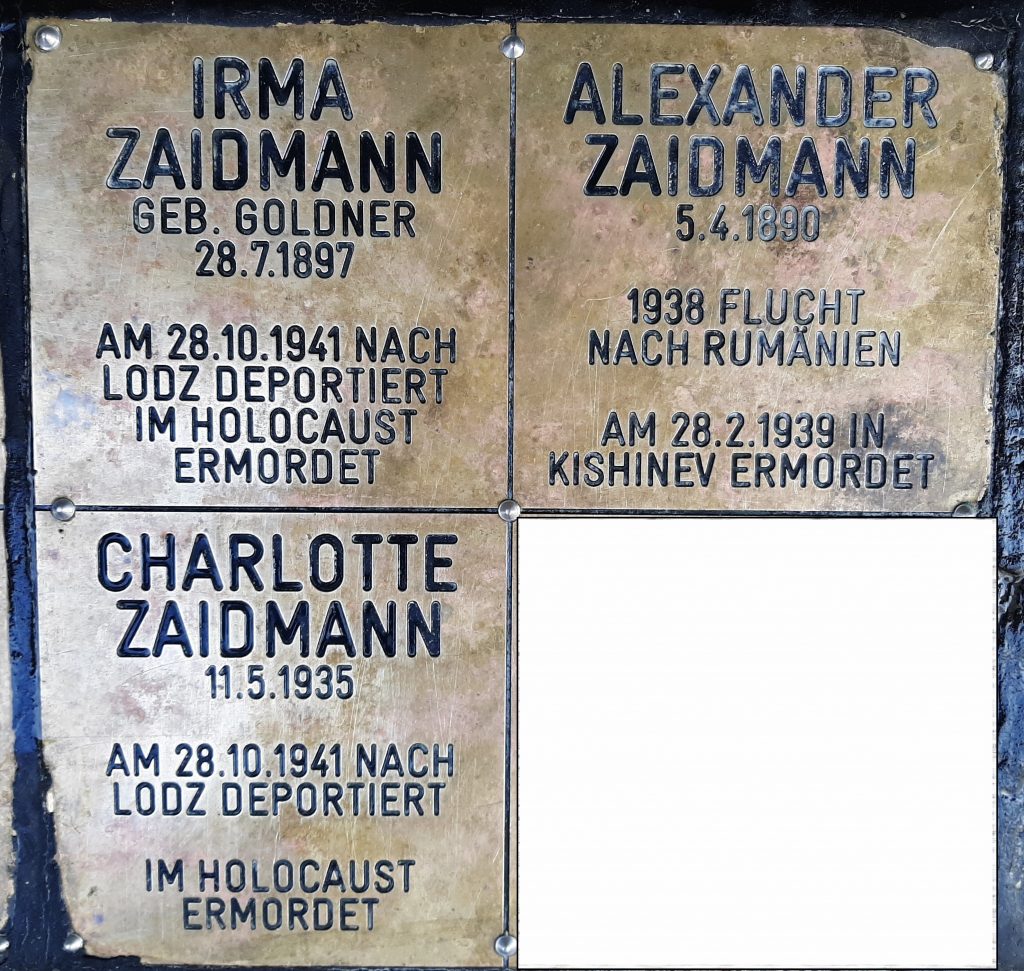

In December 2016 we reported here about our visitors from America. After this first visit to Vienna, Celia W., the daughter of a Jewish lady who had emigrated from Vienna in 1939, arranged for a commemorative plaque to be attached to the last address of her maternal relatives through the “Stones of Remembrance” association in 2018. Celia’s grandmother Irma Zaidmann was deported along with her daughter Charlotte from Herminengasse 6 to Lodz, Poland on October 28, 1941. Both were murdered in the Shoah. Celia’s grandfather Alexander Zaidmann managed to escape to Romania in 1938. However, he was murdered in Kishinev on February 28, 1939, a few months after fleeing Vienna. Celia’s mother Martha Zaidmann was able to escape to England with the help of the humanitarian rescue operation KINDERTRANSPORT and thus survived the Shoah.

During the Path of Remembrance through Leopoldstadt on May 27, 2018, a memorial plaque for Celia’s grandparents Irma and Alexander Zaidmann and for their daughter Charlotte Zaidmann, Celia’s aunt, was placed on the house at Herminengasse 6. The plaque could not be installed before the inauguration ceremony because the more than thirty homeowners did not give their consent. Since it had been incorrectly communicated that the house owners would agree to a memorial plaque being placed next to the entrance, a plaque was manufactured instead of a memorial stone (a memorial stone is usually embedded in the sidewalk in front of the house, for which only the consent of the City of Vienna is required). Two owners of a condominium in the house at Herminengasse 6 went along the Path of Remembrance through Leopoldstadt and assured the representatives of “Stones of Remembrance” and me that they were sure that all owners would give their consent at the next house owners’ meeting. In any case, they personally were in favor of the commemorative plaque being placed next to the entrance. Unfortunately, no agreement was reached at the homeowners’ meeting. The “Stones of Remembrance” association continued to try to obtain the consent of all homeowners – in vain. Eventually, I began a survey of homeowners on the subject and met a young woman who passed my concerns on to her parents, who own a condo in the house. I was struck by her father’s response, which I received by email a few days later: “An anonymous vote was taken that showed that not all homeowners would agree to the installation of a commemorative plaque. The anonymity of those voting must be respected.”

How should I explain this to Celia? Her relatives were taken from the house at Herminengasse 6 and murdered in the Shoah. They have no grave anywhere for Celia to visit to mourn. And at this last known address of Celia’s relatives in Vienna, the erection of a memorial plaque was refused anonymously and without giving any reason.

Struggling for words, I finally drew a comparison with Oskar Schindler’s birthplace, whose current owner also refuses to put up a commemorative plaque. However, it can be assumed that there are other and more concrete reasons. The former Schindler house in Svitavy, Czech Republic was expropriated due to the Benes decrees when the Sudeten Germans were expelled from what was then Czechoslovakia. According to Karl Schwarzenberg, former foreign minister of the Czech Republic, “the Benes decrees would today be considered gross violations of human rights and by today’s standards the then Czech government would probably have to answer before the International Criminal Court in The Hague.” – www.demokratiezentrum.org/wissen/timelines/bene-dekrete.html?type=98

More information about Oskar Schindler’s life story and his factory at Brnenec/Brünnlitz (today Czech Republic), where he saved 1,200 Jews from the National Socialists’ murder machine, can be seen in Werner Müller’s film documentary “Oskar Schindler’s Difficult Legacy – The Factory at Brnenec/Brünnlitz”, which was created parallel to my master’s thesis: https://tvthek.orf.at/history/Beginn-Verlauf-Auseffekten/13557936/Oskar-Schindlers-schwieriges-Erbe/14020911.

Finally, the association “Stones of Remembrance” decided to make a memorial stone and set it in the sidewalk in front of the house at Herminengasse 6. Celia will take the unused commemorative plaque with her to America on her next visit to Vienna.

Max-Winter-Platz 20, 1020 Wien

Samuel Bohensky

Cilli Bohensky

Anna Bohensky

Celia planned to come to Vienna for the inauguration of the memorial stone for her father Siegfried Bohensky’s family. However, due to the Corona-related travel restrictions, she was unable to be there on October 4, 2020 when the 14th Path of Remembrance through Leopoldstadt took place. Celia asked me to say the memorial words she had put together.

Celia had decided to have the memorial stone erected in front of the house where her father spent a happy childhood with his family (Max-Winter-Platz 20, then Sterneckplatz 20) and not in front of the house that was the starting point of the Bohensky family’s deportation. Shortly before the deportation, which the then 14-year-old Siegfried Bohensky was able to escape by emigrating to England, the family was taken to a cramped collective apartment near Herminengasse 6, where Celia’s mother already lived with her family in a collective apartment. Celia’s parents got to know each other as teenagers during this difficult time in the vicinity of Herminengasse and later miraculously met again in emigration.

The Path of Remembrance began with a ceremony at Max-Winter-Platz. The district leader was present and opened the commemorative path through Leopoldstadt with a remarkable speech. The memorial stone for the Bohensky family was the first stone to be inaugurated on the 14th Path of Remembrance through Leopoldstadt. I began to read Celia’s words of remembrance, which describe a comprehensive history of her paternal family. The inauguration was videotaped and later transmitted to Celia. Since I knew the considerable length of the words of remembrance, I tried to read them relatively quickly. However, the meaning of the words moved me and made it difficult to give an emotionally neutral, quick presentation.

Here are some quotes:

Before he left my father Siegfried gave his Bar Mitzvah signet ring to his family for them to sell so that they could buy food. He said goodbye to his father Samuel, mother Cilli and sister Anna on August 1, 1939, a day before his 15th birthday. He never saw them again.

When I came to the passage in which Celia describes how her father Siegfried Bohensky almost succeeded in rescuing his parents and sister from Vienna, I fought back tears.

On board the train to Exmouth, Siegfried sat across a man who noticed this sad, lonely, terrified young man. The man tried to speak in English to him but realized that my father spoke German. The man was a government official from the British foreign office who spoke German. Siegfried told this government official about his circumstances and his family still in Vienna and the man promised to try to get Siegfried’s parents and sister to England. The government official kept his word and started to send the necessary documents to Siegfried’s family in Vienna. But it was too late. On September 3, 1939 the United Kingdom declared war on Germany and the Bohensky family was not allowed to leave.

It was no longer possible to leave for England, with which Nazi Germany was now at war. The rescue came too late. The Bohensky family was taken to the assembly camp set up in the Jewish school at Castellezgasse 35. On February 15, 1941, together with 996 Jewish Austrians, they were driven in open trucks to the Aspang train station and from there were deported to Opole, a small Polish country town which was not prepared for taking in many people. Not even 30 of them should survive. It was the first of a total of five transports in February and March 1941, with which around 5,000 Jews were deported to small Polish towns in what was then the General Government. The abducted Viennese Jews were accommodated in makeshift dwellings and were allowed to move freely within the town of Opole, but were not allowed to leave it. They were inadequately supplied with food and used for forced labour. Most of those deported from Vienna in the spring of 1941 were murdered in the early summer of 1942 together with Polish Jews in the Belzec, Sobibor or Treblinka extermination camps (see Letzte Orte vor der Deportation – science.ORF.at – last places before deportation).

The memorial stone on the sidewalk in front of the house at Max-Winter-Platz 20 is, so to speak, the gravestone of the Bohensky family, which was initiated and financed almost eight decades after their deportation and subsequent murder by the granddaughter of Samuel and Cilli Bohensky and Anna Bohensky’s niece. The memorial stone was finally manufactured by the “Stones of Remembrance” association and embedded in the sidewalk next to the house entrance. The inauguration of the memorial stone was, so to speak, the funeral service for the Bohensky family who were murdered in the Shoah. I was not the only one fighting back tears when reading the touching words of remembrance. Celia and her family members, who later attended the memorial service at Max-Winter-Platz 20 by video recording at their home in California, could not hold back their tears.

As soon as it is possible to travel from America to Austria again, Celia would like to revisit Vienna together with her husband Allen. It will be my privilege this time to take them to those places in Vienna that are particularly reminiscent of Celia’s families of origin, Zaidmann and Bohensky.

Elisabeth Baumegger (February 15, 2021)

o